Written by Todd Goehle

On 4 June 2020, 26.5% of those hospitalized from COVID-19 in Onondaga County were Black. And yet, only 11.4% of the county’s total population is Black. As outlined within PEACE, Inc.’s COVID-19 Community Needs Chronicle and Assessment, the inequalities of our past continue to haunt our pandemic present. For the full assessment, visit the agency’s website. In the article below, Todd Goehle walks us through some of the major findings.

Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the lives of Central New York residents. But what does this mean? Who is struggling? And in what ways? How can different forms of data be used to mobilize resources? To adjust antipoverty services effectively? To help those who are most vulnerable? In May, PEACE, Inc.’s Community Engagement Team began to research these questions. Our efforts became the COVID-19 Community Needs Chronicle and Assessment.

The team analyzed data from national, state, and local foundations, governments, and sources. We met with community leaders, staff members, and agency clients. Client case notes were collected as well. The team also used the Central New York Community Foundation’s Life Needs Assessment Survey, receiving 230 responses over the course of 11 days in May. Through our research, the assessment comprehensively explores the pandemic’s effects on Physical and Mental Health; Youth, Family, and Senior Supports; Food and Nutrition; Employment; Education; Childcare; Housing; Access to Capital; Technology; Access to Information through informal networks and media; gender; and race and ethnicity.

Findings

Two findings are noteworthy. First, the majority of the problems seen during the pandemic are not new per se. Rather, COVID-19 has intensified long-standing structural insecurities and inequalities.

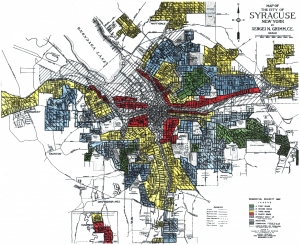

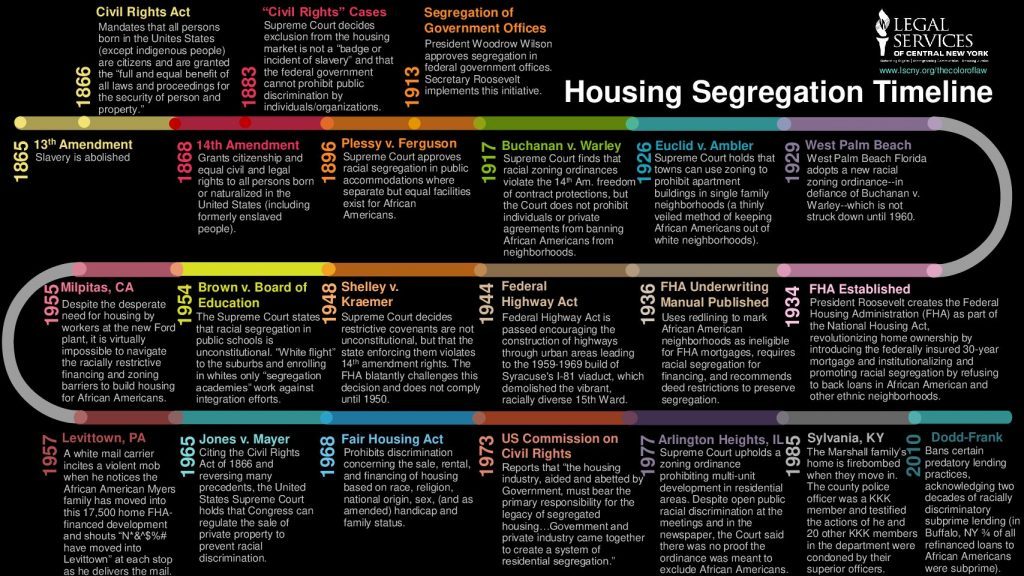

So what do these complicated ideas mean? It starts with this map of Syracuse:[1]

The map was produced in 1937 by the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency that assigned neighborhoods 4 investment “ratings” and thus guided mortgage lending. The “riskiest,” rated “Hazardous” and colored “Red,” were based upon building conditions and racial demographics. Here, residents of color were unable to access federal loans. In “Definitely Declining” or “Yellow” neighborhoods, only 15% of residents could receive backing. Banned in 1968, “redlining” created obstacles for Black homeownership, a means for growing personal wealth historically. Redlining furthered financial disinvestment. And it deepened chronic poverty in communities of color.

Redlining, poverty, and issues of race, employment, and health have been well-documented in Syracuse.[2] More recent research by the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) found that 3 of the 4 ZIP codes with the highest COVID-19 case rates had large portions of yellow or redlined neighborhoods.[3] Past and present disparities are linked. County health statistics also confirm how people of color are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 in Onondaga County.

Onondaga County COVID-19 Cases by Race and Race as Percent of Population (4 June 2020)[4]

| Race | Percent Hospitalized by Race | Race as Percent of Population |

|---|---|---|

| Black or African American | 26.5% | 11.4% |

| White | 59.8% | 79.9% |

| Other | 9.2% | 8.7% |

| Unknown | 4.5% | 0.0% |

During the pandemic, cities across the country have declared racism as public health crisis.[5] With the legacies of redlining clear, the research of NYCLU and now PEACE, Inc. supports this claim for Syracuse.

A second key finding from the assessment: those most vulnerable in the COVID-19 pandemic lack multiple basic needs. Social Determinants of Health interact and reinforce one another to impact a person’s ability to remain healthy. Let’s address food and poverty.

Throughout the pandemic, the community has worked hard to provide nutrition for those in poverty. At PEACE, Inc., only 9.7% of nearly 230 Life Needs Assessment Survey respondents answered that they lacked food.[6] Still, as NYCLU noted, significant portions of those Syracuse ZIP Codes most impacted by COVID-19 are both “redlined” and classified as food deserts.[7] Poverty is layered. For example, nearly 40% of survey respondents “spend time alone more often than they would like.”[8] More than a third lack the technology to “meet needs for work, school, or other responsibilities.”[9] How might matters of socialization connect with hunger? The closing of Senior lunches and congregate meal sites has left low-income seniors both food insecure AND isolated.[10] Senior “Meals-to-Go” services have provided nutrition and smiles for those forced to remain at home. Yet the data reveals the smiles might only be temporary. The African proverb rings true, “One who eats alone cannot discuss the taste of the food with others.”

Other examples from the assessment are telling. An elderly woman raising 2 of her grandchildren can pay for groceries but lacks a car and has health conditions that make her nervous to ride the bus. A single mother struggles to cook -let alone to shop- due to a lack of home supports for her disabled child. A recently unemployed man who went to a food pantry for the first time now feels shame that he could not provide for his family. Food must be placed within wider contexts of poverty

For Action Steps, 3 policy suggestions can be recommended:

1) Services must be multifaceted, meet immediate need, and foster systematic change. The research reveals how trauma-informed services, local interventions where poverty is highest, and affordable Internet for impoverished families are just 3 examples that address long-standing inequalities and meet multiple needs.

2) Nonprofits must have difficult, inclusive conversations. By connecting the COVID-19 pandemic with longstanding inequalities, the assessment questions the effectiveness of our community’s antipoverty initiatives. It provides starting topics to advance conversation and change. And it supports the need for a) the rising community advocacy of recent months, b) more inclusive public forums, and c) equitable reform.

3) Building a Culture wherein Data is accessible to all. Like CNYVitals, the assessment provides public research and data. More transparency is needed, however. We hope critical assessments will spur partnerships and help local agencies value sharing data publicly. Defining the terms that we use to measure poverty can also challenge our underlining assumptions about it. Most think “Redlining” is bad. But can we explain it? Or connect it with the lived experiences of its victims? Trainings for staff, “lunch and learns” with the community, as well as monthly 1 to 2-page overviews are just some ways in which data can become more inclusive and equitable.

About PEACE, Inc.

Incorporated in 1968, People’s Equal Action and Community Effort, Inc. (PEACE, Inc.) is the federal designated Community Action Agency (CAA) for Syracuse, Onondaga County, and portions of Oswego County. The agency’s mission, “to help people in the community realize their potential for becoming self-sufficient,” defines its 9 antipoverty initiatives: Head Start, Family Services, Department of Energy and Housing, Senior Nutrition, Foster Grandparents, Senior Support Services, Eastwood Community Center, Big Brothers Big Sisters, and Free Tax Preparation.

[1] Map retrieved from Central New York Community Foundation. (18 May 2018). “How the History of Redlining and I-81 Contributed to Syracuse Poverty.” CNY Vitals. Retrieved from https://www.cnyvitals.org/how-the-history-of-redlining-and-i-81-contributed-to-syracuse-poverty/.

[2] See Ibid.; Onondaga County Health Department. (June 29, 2017). “Mapping the Food Environment in Syracuse, New York 2017.” Retrieved from http://www.ongov.net/health/documents/FoodEnvironment.pdf; and Urban Jobs Task Force (UJTF) and Legal Services of CNY. (2019) “Building Equity in the Trades: A Racial Equity Impact Statement.” Retrieved from https://www.ujtf.org/reis.

[3] NYCLU. (May 18, 2020). “Testimony of the New York Civil Liberties Union before the New York State Senate and the New York State Assembly regarding the Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Minority Communities.” Retrieved from https://www.nyclu.org/sites/default/files/field_documents/20200518-testimony-coronavirusracialdisparities.pdf.

[4] PEACE, Inc. (2020). COVID-19 Community Needs Chronicle and Assessment. Retrieved from https://www.peace-caa.org/about-us/covid-19-community-chronicle-and-needs-assessment/.

[5] Vestal, Christine. (15 June 2020). “Racism is a Public Health Crisis, says Cities and Counties.” PEW Charitable Trusts. Retrieved from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/06/15/racism-is-a-public-health-crisis-say-cities-and-counties.

[6] PEACE, Inc.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid.

[10] Eisenstadt, M. (May 1, 2020). “Crews bring lasagna and connection to the locked-in elderly starved for a friendly face (video).” Syracuse.com. Retrieved from https://www.syracuse.com/coronavirus/2020/05/crews-bring-lasagna-and-connection-to-the-locked-in-elderly-starved-for-a-friendly-face-video.html

Recent Comments