AN ANTI-POVERTY PROJECT: This is the first of many essays to be released by PEACE, Inc. and Ocesa B. Keaton LMSW, executive director of Greater Syracuse H.O.P.E.

Each month, they will explore different dimensions of an issue that affects all Central New Yorkers – poverty. They will unpack topics that are frequently discussed but perhaps not well understood. Additionally, they will present accessible tools to engage/inform people, to build coalitions and to advance policies for change.

REDLINING. URBAN RENEWAL. Each are terms that many are recently hearing for the first time. The former sounds negative. The latter – on the surface – sounds positive. Yet what are they? Why have these terms emerged as ways for understanding American cities – including Syracuse – and the racial inequalities that plague them? How have these policies helped to concentrate power in the hands of a few and to create poverty among communities of color? How have the vulnerable challenged the inequality introduced by REDLINING, URBAN RENEWAL, and more? In response, we look to answer these questions and begin our broader paper series by contending that the past can shed light on our city’s current plights and inspire the many community reform movements seen at present.

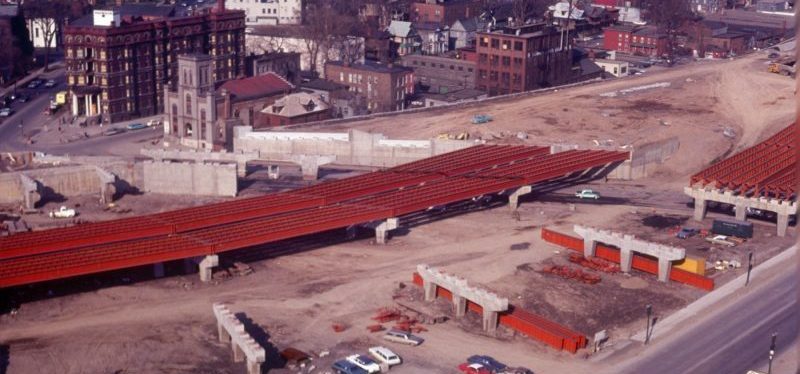

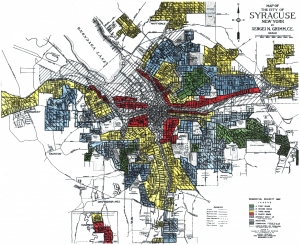

Like other American cities in 1937, Syracuse and its neighborhoods were assigned 4 categories or “colors” by the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a newly created federal agency. The categories were mapped to guide investment and mortgage lending during the Great Depression. Still, the promise of economic recovery for all fell short, as categories were based upon the neighborhood’s housing conditions and racial demographics in particular. The “riskiest” neighborhoods -rated “Hazardous” and colored “Red-” were African-American communities who were denied home loans. In locations deemed “Definitely Declining” or “Yellow,” only 15% of the residents could access loans. Reversed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, REDLINING nonetheless prevented Black homeownership and deepened disinvestment in communities of color.

A 1937 Map of “Redlined” Syracuse by the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (University of Richmond)

African-American neighborhoods in Syracuse were not immune to this policy. Near the city’s downtown, the 15th Ward provided a space for African-Americans escaping the racial violence of the American South and the broader discrimination of Central New York. A former resident perhaps described it best when he described the 15th Ward, “Back then, all the blacks lived near each other… That’s how everybody knew each other. And blacks could only rent in certain parts of the city, so that’s why they ended up in the 15th Ward, because whites wouldn’t rent to them on the East Side, on the North Side, on the West Side or the South Side.” (The Stand) Landmarks such as SUNY Upstate medical complex, the Jefferson and Madison Tower Apartments, and I-81 now stand where the 15th Ward once stood. More on this in a minute.

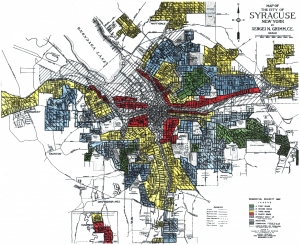

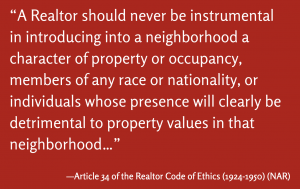

The earlier description of the 15th Ward reflected the effects of non-governmental practices such as Article 34 of the National Association of Real Estate Boards (see below). But such discrimination was also a product of the law, and it wasn’t only Redlining. For example, the Housing Act of 1937 held a provision that, among other policies, allowed for what was described as “slum clearance.” In Syracuse, this led to the creation of Pioneer Homes, one of the nation’s first public housing initiatives. Interestingly, Pioneer Homes was originally intended for whites only. Through the actions of African-American organizations such as the Dunbar Community Center, some degree of integration became possible. (Stamps, 56) Herein lies an important point. As new systems of racial inequality were created, Syracuse’s small but growing Black community challenged them.

Founded by a former slave, the PEOPLE’S AME ZION CHURCH is the oldest Black congregation in Syracuse. It was located at the above site, 711 E. Fayette Street, from 1910 to 1975. The church served as a cultural center for the 15th Ward’s Black community and a site for civil rights activities. There are continued attempts to refurbish the church, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. (PACNY)

Later amendments, specifically the Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954, provided additional resources for public housing, slum clearance, and private development. (Rothstein) Such acts of URBAN RENEWAL were accompanied by laws such as the Federal Highway Act of 1956, which looked to interconnect the economies of American cities through 41,000 miles of Interstate. As wealth moved to the suburbs, restrictive covenants –or legal requirements written about a property included in the deed– continued to prevent African-Americans from purchasing homes and ensured “white-flight” was indeed white. In the name of economic “progress,” Urban Renewal cleared blighted properties and relegated African-Americans to declining neighborhoods, leading author James Baldwin and others to describe it as “Negro Removal.”

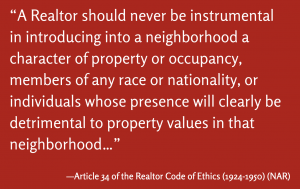

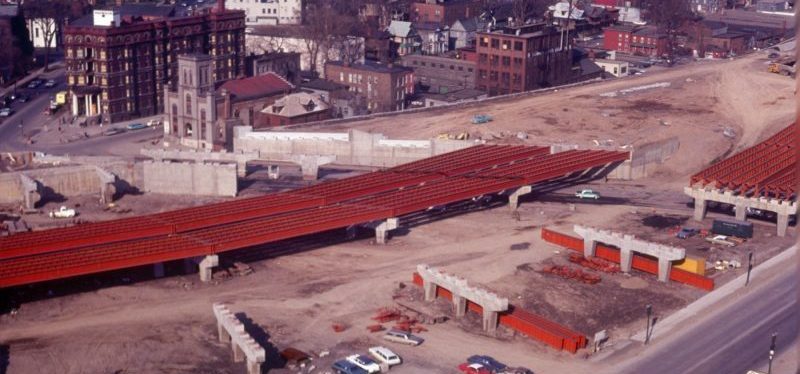

Such processes affected Syracuse and its downtown as well. For example, the first of the two AXA Towers that currently define the city’s skyline was originally built as the MONY Building in 1966 and was one of the larger accomplishments of the initial “Downtown-I” urban renewal project. (Knight, 17) Most notorious however was the construction of the I81 Viaduct. It physically destroyed the 15th Ward and caused the removal of an estimated 900 African-American families from their homes, and affected more than 80% of the city’s black population at the time. (Stamps, 81; Knight, 10) Here the literature is increasingly extensive; references to a few of the studies can be found at the end of this document.

Less discussed are the forms of African-American resistance against government-sanctioned removal. Mirroring national developments, Syracuse residents also used advocacy to advance social justice, which helped enact policy and create reform with the aim to improve the conditions of African-Americans. For example, the passing of the aforementioned Fair Housing Act of 1968, which outlawed much of the housing discrimination outlined in this text, came during a time of unrest, specifically the national civil rights movement and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Previous attempts to pass such a bill had failed due to a lack of Congressional support. In Syracuse, the destruction of the 15th Ward and the racial discrimination which prevented its residents from securing quality housing were catalysts for protest. Impacted residents formed groups to present their demands to elected officials. Two of them—the Southside Home Owners Association and the Eastside Cooperative Council– delayed construction of I-81 by two years due to demands of fair pay for the sale of their home. Formed by Dunbar, the Eastside Cooperative Council consisted of human agency groups that served the Eastside of Syracuse. (Stamps, 83) The Council was able to serve as a conduit for information between the community and representatives of the Urban Renewal Program. The council actively worked to create a relocation plan and helped lay the groundwork for the creation of the Relocation Office in 1959. (Stamps, 83)

Later in 1963, The Congress of Racial Equity (CORE) organized protests against the urban renewal in Syracuse. The protest included directly confronting city officials, blocking construction sites, and sitting on cranes to stop demolition work. CORE remained a prominent fixture in the Syracuse community and helped to organize other protests with the goals of creating a more inclusive city for African-Americans.

Insertion of Steel Placements, April 1967 (DOT)

IN CONCLUSION, one might ask, why focus on the past? What does history have to do with nation-leading rates of poverty among Black and Brown peoples in Central New York? Why start here? For us, understanding the policies that produced an unequal past -such as REDLINING and URBAN RENEWAL– helps us better understand the conditions that shape our unequal present. Within the past decade, national and local research has shown how the highest rates of concentrated poverty, lead, obesity, gun violence, COVID-19 hospitalizations, and more exist within Syracuse’s previously red– and yellow–lined neighborhoods. In other words, the legacies of REDLINING and URBAN RENEWAL are still seen and negatively felt every day. They are legacies that have established a STRUCTURAL INEQUALITY wherein persons of color in particular have lacked equal access to resources, decision-making, opportunity, and the law. As noted, research has exposed these negative legacies. Yet so too has a mobilized local community that -in this moment of the Black Lives Matter movement, the George Floyd killing, and debates about police reform– once again draws inspiration from national developments. And therein lies a final critical point for looking at the past. One that is perhaps more positive and hopeful. It is to see how those most affected by structural inequality have always combated and challenged it. That they have not been silent in the face of repression.

Next month, we will continue the series. We will discuss HOUSING and poverty to further explore this concept of STRUCTURAL INEQUALITY. Until then.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 1) Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America: The University of Richmond’s interactive website that includes original HOLC maps of American cities and descriptions of graded neighborhoods (including Syracuse). 2) In 2019, The ROOT published a YouTube video, How Redlining Shaped Black America, that effectively outlines the racist legacies of redlining on American cities today (Warning: Strong Language is used). 3) NewsChannel 9 with its “Hidden History: The End of the 15th Ward,” WAER’s “City Limits: A Poverty Project,” and the Onondaga County Historical Association with a special exhibition each released reports about the 15th Ward of Syracuse in 2019.

FOOTNOTES AND SOURCES

Bridge Street. “Remembering the 1963 CORE Protests.” WSYR, February 22, 2018. https://www.localsyr.com/bridge-street/asseen-on/remembering-the-1963-core-protests/. Knight, Aaron C., “Urban Renewal, the 15th Ward, the Empire Stateway and the City of Syracuse, New York.” Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects, 590, 2007. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/590. New York State Department of Transportation. “History of Transportation in the City of Syracuse.” I-81 Viaduct.

New York State Department of Transportation (DOT), 2020. https://www.dot.ny.gov/i81opportunities/history.

“Mapping Inequality, Redlining in New Deal America: Syracuse.” Digital Scholarship Lab, 2020. https://dsl.richmond.edu/ panorama/redlining/.

“1924 Code of Ethics.” National Association of Realtors (NAR), 2020. https://www.nar.realtor/about-nar/history/1924-code-ofethics.

“PACNY Celebrates Black History Month.” Preservation Association of Central New York (PACNY), 2013. http://pacny.net/ home/.

Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: a Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

Stamps, Spurgeon Martin David, and Miriam Burney Stamps. Salt City and Its Black Community: a Sociological Study of Syracuse, New York. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2008.

“Vision.” Greater Syracuse H.O.P.E., 2019. https://www.greatersyracusehope.org/.

About the Authors: Todd Goehle is Planning/Community Engagement Manager at PEACE, Inc. and previously a SUNYAward Winning Lecturer of History and Humanities. Ocesa B. Keaton is Executive Director of Greater Syracuse H.O.P.E. and a Licensed Social Worker. To learn more about the project, reach out to Community.Engagement@peace-caa.org.

Recent Comments